Issue 3: The British Library

Does the controversy surrounding some of London's most famous public buildings affect our understanding of modern architectural intent?

Although my interest primarily lies within residential architecture and trends, I recently visited the British Library and it made me consider how the controversy surrounding some of London’s most famous public buildings affects our understanding of modern architectural intent.

The British Library has been critiqued for decades, with Prince Charles labelling the building as “a dim collection of sheds groping for some symbolic significance”. I don’t doubt this statement was fuelled by frustration - the British Library was nearly 10 years behind schedule, £350m over budget and a project manager’s worst nightmare. The development was victim to varying political agendas - local MP’s pressured the Government to renounce the Bloomsbury site, then 18 months later commissioned a redesign from architect Colin St John Wilson as they concluded the initial site was most suitable, this was short lived as Kings Cross became the final site. Governments frequently reduced the budget triggering multiple redesigns and even intended to sell the land needed for the next phase of work. Growing concerns allowed room for incompetency, construction quality was lousy and contractors were not penalised for underperformance, this continued to escalate whilst the Government failed to intervene. Following reports of mismanagement and sabotage, the National Audit Office launched an investigation that detailed the Government’s illogical planning, weak management and failure to predict costs.

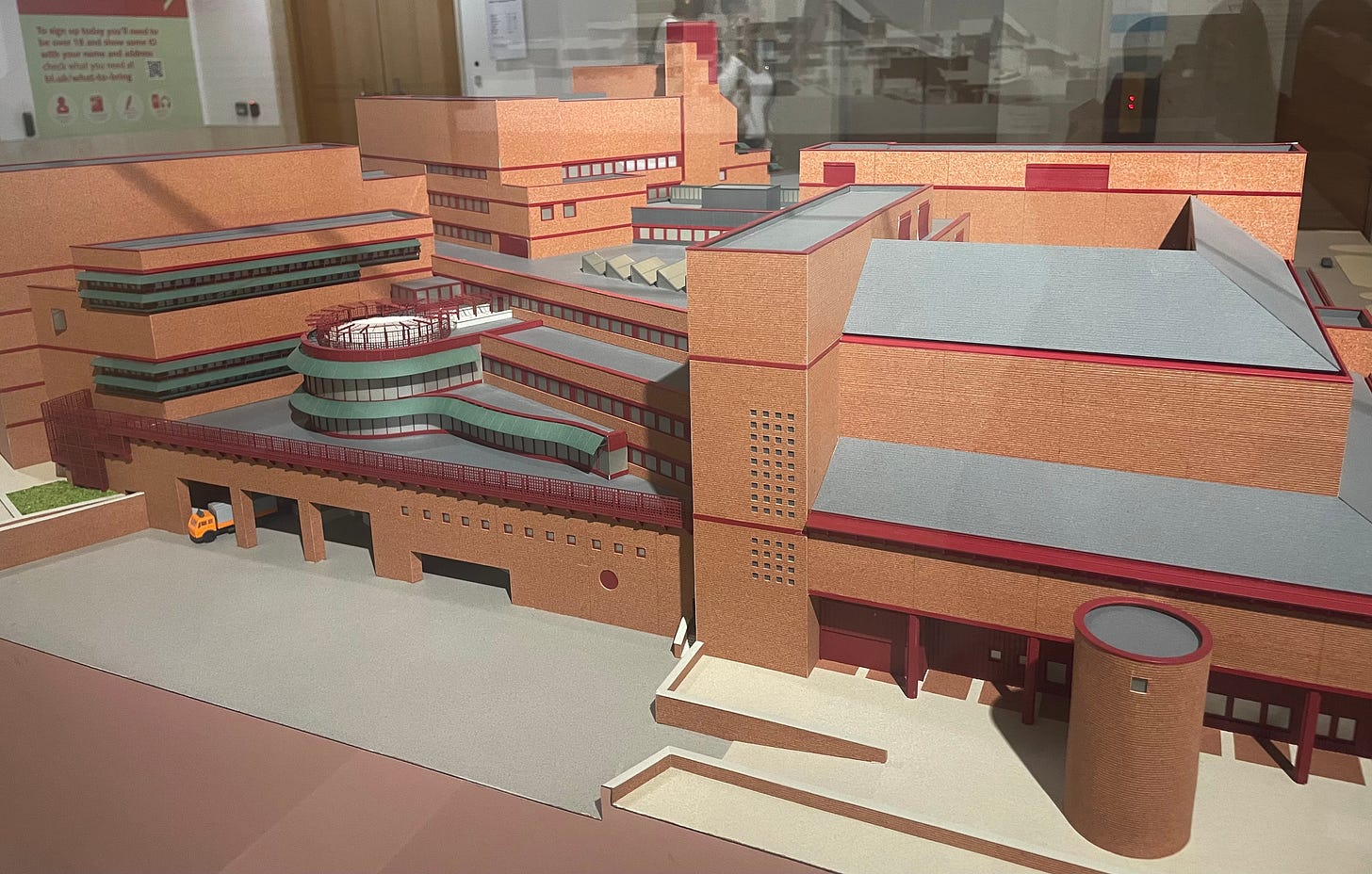

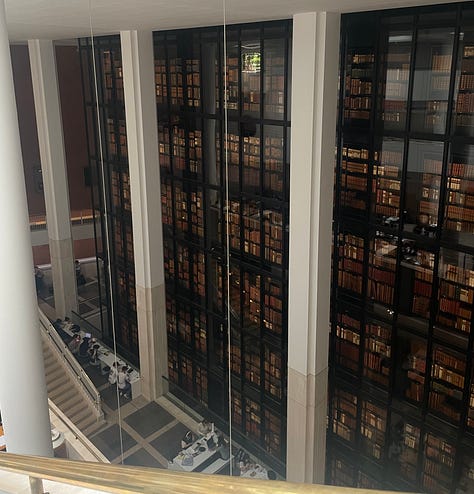

The chaos surrounding this development made it easy to resent a design style that is often perceived as miserable and unwelcoming. In fact, the architect, Colin St John Wilson named his involvement with the British Library his “30-year war”, confidence in his architectural firm whom he’d shared with his wife, M. J. Long was dwindling, and his subsequent design of the Liverpool Civic and Social Centre was described as fascist and was scrapped. In light of this, it is easy to overlook Wilson’s architectural intent for the British Library. Architects leaned into post-war modernism particularly for public buildings and social housing to symbolise progress and functionality - a key criticism of the style as the public often felt such designs failed to prioritise liveability. Whilst the architectural style may not be to everyone’s liking, Wilson thoughtfully considered the influences for the building, from the red brick that mirrors St Pancras station and Cambridge University, to it’s ship like structure. The interior has numerous features that gives way to Wilson’s architectural intent, including leather wrappings of the handrails that mirrors book bindings, natural light and rising ceilings to stimulate thought and the six story glass tower containing the Kings Library.

The British Library was awarded Grade I listed status in 2015, a rare award with only 2.5% of listed buildings receiving Grade I. It is one of the youngest buildings to be awarded listed status and this will ensure its design will be protected similarly to its neighbours the St Pancras Hotel and Kings Cross station.

Whether you are a fan of modernist architecture or not, the architectural intent of the project should receive great appreciation. Considering the endless meddling and incompetencies, a traditional style library would have also faced a similar struggle.